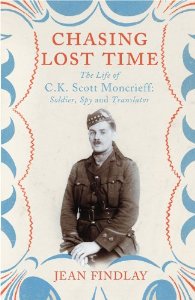

Jean Findlay, Chasing Lost Time: The Life of C.K. Scott Moncrieff, Soldier, Spy and Translator. Chatto and Windus, London, 2014, pp.351

What would C.K. Scott Moncrieff, a notoriously caustic reviewer in his day, make of his great-great niece’s biography? He would no doubt be delighted that this project had been undertaken by one of the descendants of the family he worked so hard to provide for, and touched by the obvious admiration and sincere affection with which Findlay weaves her narrative. This is an accomplished and compassionate biography which finally gives shape to the eventful life of a man who has until now been merely a footnote in the biographies of others. Her achievement is all the more notable since, as her introduction hints (p.3), it was researched and written at the same time as raising young children.

The biography is unashamed in its sympathy with Charles. This is a very different portrait of Scott Moncrieff to that glimpsed in published accounts elsewhere. Indeed until now, the picture of CKSM encountered by readers of literary biography has been largely based on the opinions of those he alienated: Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, DH Lawrence, the Sitwells. Thus in Dominic Hibberd’s works on Wilfred Owen he emerges as a vaguely sinister, predatory homosexual, while David Leavitt’s Florence: a Delicate Case takes its cue from bookseller Pino Orioli’s memoir, portraying him as unloveably quarrelsome and a religious fanatic. Neither depiction bears much resemblance to the Charles lovingly reconstructed by Findlay. Her Charles is a man of honour: loyal, kind and unstintingly generous to friends and family. This is not to say that he is one-dimensional. Charles’ letters to Vyvyan Holland, the younger son of Oscar Wilde, provide much colour and help dilute the image of an overly earnest man of letters, dutiful son and brother and pious Catholic, gleaned from extant correspondence with literary acquaintances and family members.

However the book is not without its flaws, one of which is a sloppiness with chronology, and in particular, ages. For instance, on one page Christopher Millard is ‘ten years Charles’ senior’ (p.50) but later ‘36 when he met the 16 year old Charles’ (in fact he was 17 years his senior and Charles was almost certainly already 17). At another point a portrait of Charles painted in 1919 is described as being painted in 1922. These errors are not so much Findlay’s fault as her editors. But elsewhere Findlay gets her facts plainly wrong. Millard was not living at Abercorn Place in 1906. He did not live there until 1919. In the spring of 1907 he was staying at his brother’s vicarage in Forest Gate. Similarly, Robbie Ross did not move into 40 Half Moon St until during the war. Puzzlingly these facts are all given in books which Findlay herself lists at the back of her book. Neither was Bonar Law’s son, also called Charles, at school with CKSM, since he went to Eton and only qualified for active service in 1916. This information is freely available from google. But to point out such inaccuracies is mere pedantry.

More frustrating are those sections where Findlay appears to overlook the available literary evidence on which her interpretation of Charles’ personal life relies. Charles might be dismayed to read that he was, by 1918, simply too physically repulsive to seduce Wilfred Owen. Findlay is insistent that there was no sexual relationship between them, despite the many clues in Charles’ love sonnets to the young poet. Is a man who will sexily pun on ‘putting one’s nephew into a tube’ really likely to be oblivious to the innuendo in ‘my night’s swallowing thee’? (p.148) Findlay is naturally keen to absolve Charles of what Robert Graves made sound like date rape (p. 319), but her claim that the ‘conservative and law abiding Owen’ would not have welcomed any sexual advance sounds vaguely fanciful. Until, that is, Findlay acknowledges her indebtedness to Jon Stallworthy, who has been carrying on a proxy war to ‘degay’ Owen since Hibberd’s death in 2012.

At the same time Findlay gives disproportionate precedence to the friendship above other far more permanent and important relationships. She writes that Owen’s death ‘left a crater in Charles’ life’ (p. 162) and describes his dedicatory poem to Owen in the Song of Roland as embodying ‘the sort of sentiment a man would write on his wife’s tombstone’ (p.161). Fair enough, until one reads Charles’ dedication to Philip Bainbrigge, his ‘closest friend’ since 1910, which he himself gave precedence over his sonnet to Owen:

Mind of my intimate mind, I may claim thee lover:

Thoughts of thy mind blown fresh from the void I gather;

Half of my limbs, head, heart, in thy grave I cover:

I who, the soldier first, had at first designed thee

Heir, now health, strength, life itself would I give thee.

More than all that has journeyed hither to find thee,

Half a life from the wreckage saved to survive thee.

On the strength of this poem I would suggest that if anyone had a claim to being Charles’ ‘wife’ it was Bainbrigge, though the sonnet dedicated to Owen admittedly establishes him as the ‘master-mistress’ of his passion.

None of this is to deny Findlay’s achievement in rescuing her great-great uncle from obscurity, and it is to be hoped that her book will acquaint a new readership with the enigma of Scott Moncrieff and provide a fitting accompaniment to the current revived interest in his translation as we approach its centenary.