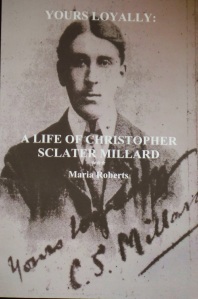

Maria Roberts, ‘Yours Loyally’: A Life of Christopher Sclater Millard, (Feed-A-Read, 2014), pp. 304

In 1914 on the eve of war, Christopher Sclater Millard published his complete bibliography of Wilde’s published works. At over 600 pages, the volumes marked the culmination of over ten years research and contained a staggering wealth of information about Wilde’s literary production and is a testament to Millard’s dedication to the task and personal enthusiasm for the subject. Robert Baldwin Ross, Wilde’s literary executor called it ‘an astonishing and ingenious compilation’ while his friend and lover C.K. Scott Moncrieff described it as ‘the first good bibliography, and still the best in our language’. Millard himself thought it ‘the only thing I am likely to be remembered by to my merit!’

Exactly a hundred years to the month, Maria Roberts has published a new biography of Millard. The first was a fragmentary study by the late H. Montgomery Hyde, which brought together much new information but did not attempt to weave it into a cohesive narrative as Roberts has done. However any aficionado of the art of bibliography or the Wildean cultural milieu may be disappointed with this book. For it is not a scholarly enquiry into the cultural production of Wildeana, nor does it have anything new to say about Wilde’s circle. Instead it is something far more interesting: an attempt to reconstruct the life of a remarkable and original individual, an openly and unashamedly gay man living in a society which criminalized all sexual acts between men, for whom the rehabilitation of Wilde’s genius was not merely a personal enthusiasm but a form of political activism.

Michael Davidson, Christopher Millard’s ‘young man’ at the the time of his death at just 54, later suggested that Millard’s claim to greatness lay not in his literary accomplishments, but in his personality. Meeting him was, Davidson recalled, ‘like climbing up Olympus and having drinks with one of the nicer gods’. It is Christopher Millard, the man, who is the subject of Roberts’ book.

Yet despite Roberts’ best efforts, Millard remains an enigma. Born in 1872, he was just 22 when Oscar Wilde was convicted of gross indecency and sentenced to two years hard labour. At the time he was a student of theology at Salisbury where he was training for the ministry, and Roberts believes he was already in a relationship with another man. Yet while the scandal had a largely disciplinary effect on many gay men (Edward Carpenter, who Millard admired, declared that ‘The Wilde trial had done its work and silence must henceforth reign on sex subjects’), Christopher was moved to write to Reynolds Newspaper to defend Wilde and descry his treatment by the press. ‘Because a fellow creature has fallen’, he wrote, ‘why should they cast stones at him? Are the writers of such articles themselves immaculate in their passions?’

The shadow of the Wilde trials hangs ominously over Roberts’ narrative. Though he had admired Wilde’s poems and plays beforehand, Wilde’s prosecution had a profound affect on Millard. From this time he appears to have been consumed by his interest, obsessively collecting anything to do with Wilde, including thousands of newspaper clippings, reviews and caricatures which he compiled in scrapbooks now preserved in the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library. In 1904 he left his post as Headmaster of a small private Catholic school to devote himself to the considerable task of compiling an authoritative bibliography of Wilde’s published works.

But in the summer of 1906, Millard suffered the same fate as Wilde. He was arrested following a drunken and ill-judged pass at a young man called Thomas Bradbury, and sentenced to three months hard labour in Oxford Prison. Yet unlike Wilde, Millard did not (to his family’s chagrin) leave England to begin a new life on the Continent, instead staying on to contend with the prejudice and persecution which his conviction left him open to. One of the most interesting chapters in Roberts’ book draws on the police reports collected on Millard by Scotland Yard in 1914-15. Millard was placed under surveillance following his involvement with Charles Nehemiah Garratt, a seventeen year old suffragist and prostitute, who was for a time his lover. Roberts’ use of the PRO documents follows the work of Matt Houlbrook in reconstructing the homosexual subculture in which Millard moved, and which in 1916, led to a second warrant being issued for his arrest.

Remarkably, Millard refused to be cowed either by his imprisonments or the opprobrium with which he was treated by polite society. He was in fact entirely open about his ‘rows’, as he called them, ‘regarding them as accidents which having happened, no honest man would want to conceal’, and ‘out and proud’ more half a century before Stonewall. When in 1920 he was employed by Vyvyan Holland to edit an edition of Wilde’s letters to Ross, Millard defied Holland’s instructions that all homosexual material should be removed. ‘It was very wrong of you to put the Uranian passages in after my very careful deletions’, wrote Holland. ‘But I forgive you, knowing how earnest you are in your devotion to the subject… I won’t have the letters used as Uranian propaganda’.

Roberts’ writes with an empathy and enthusiasm for her subject which nonetheless does not spill over into panegyric. The inevitably low production values of print-on-demand publishing do not do justice to her careful and detailed reconstruction of Millard’s life and milieu. This book is recommended reading, not merely for devotees of Wildeana, but anyone interested in the history of sexuality and the social and cultural aftermath of the Wilde trials.